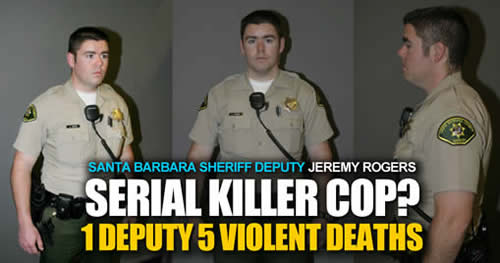

Does Jeremy Rogers Look for Trouble, or Does Trouble Find Him?

Most law enforcement officers go their entire careers without ever firing their gun in the line of duty. In fact, according to a recent national survey of nearly 8,000 cops across 54 cities and counties, only 27 percent said they have ever used their service weapon on the job.

Yet in just 15 years of working for the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office, Deputy Jeremy Rogers has been involved in three shootings, all of them fatal. The first resulted in a wrongful-death lawsuit. The second prompted allegations of excessive force. The third remains under investigation.

Rogers, it seems, has a knack for putting himself in the middle of the action. In 2017, he helped evacuate hundreds of people trapped at Camp Whittier by a fast-moving wildfire, which earned him an award for bravery.

But earlier in his career, he also inadvertently caused a head-on collision during a wrong-way DUI pursuit that killed two people, maimed another, and led to a negligence claim that cost Santa Barbara taxpayers $4.8 million.

Rogers remains on active duty with the Sheriff’s Office, and it is unknown if he has ever been disciplined for any of the aforementioned incidents. The department won’t say. The Sheriff’s Office would also not disclose what specific assignments and posts Rogers has held, where he is currently stationed, or if any other public complaints have been lodged against him.

“Your questions are outside of the scope of what I can release,” said Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Raquel Zick. Rogers did not respond to direct requests for comment.

The information in this article was obtained primarily through a California Public Records Act request filed by the Independent in June, following the death of George Floyd and amid renewed scrutiny over how and when law enforcement officers use physical force against civilians.

Whether Rogers is ultimately a sinner or a saint is a matter of debate. Policing is stressful, challenging, and traumatic work, and his deeds may indeed be justifiable. What deserves equal consideration, however, is that such lethal behavior by Rogers and others is in fact trained, protected, and vigorously defended by American law enforcement culture.

Santa Barbara sheriff’s deputies, like many of their counterparts across the country, are given a wide latitude when deciding in the heat of the moment to use lethal force. They must “reasonably believe,” the department’s policy manual says, that they or others are facing an “imminent threat” that would result in serious injury or death. The local law enforcement bodies that scrutinize shootings ― the Sheriff’s Office Shooting Review Panel and the District Attorney’s Office ― use equally broad discretion in deciding what was “reasonable” at the time and how “imminent” the threat truly was.

Sheriff Bill Brown stands by Rogers and his record. “Deputy Jeremy Rogers continues to serve the people of Santa Barbara County honorably and courageously,” he said in a prepared statement.

“His duty to protect the community has placed him in harm’s way on numerous occasions. The three shootings he has been involved in, while tragic, were all precipitated by the actions of criminal suspects. All three shootings were meticulously investigated. Two of them have been deemed to be within Sheriff’s Office policy, and a Shooting Review Panel will convene later this month to review the last shooting. Each shooting was also independently reviewed and found to be justifiable under the law by the District Attorney.”

Rogers, 40, was born in Oklahoma and went to college in Texas, where he worked as a jail guard for three years. He then spent two years as a correctional officer at the federal prison complex in Lompoc before joining the Sheriff’s Office. During his training, superiors noted he had difficulty following directions and managing his impulses.

In an interview with detectives following his second shooting, Rogers briefly talked about his motivation for becoming a peace officer. “My cousin was killed by a wrong-way drunk driver,” he said. “That had an effect on why I chose this profession.”

Santa Barbara Sheriff Deputy Jeremy Rogers Shooting #1

Donald George, recently disabled by brain surgery, was standing at his walker and holding a gun when he was shot. | Credit: Courtesy

Donald George had recently undergone surgery to remove a brain tumor when he was shot and killed by Rogers and two other deputies on March 6, 2008. The procedure, which didn’t go well, left the 64-year-old retired engineer and Vietnam veteran highly compromised and severely depressed. He had difficulty speaking, could barely hear, and used a four-wheeled walker to get around.

At 7:44 a.m. that morning, George’s wife of 40 years, Carol, frantically called 9-1-1 because he’d retrieved the loaded handgun he kept in his truck and was threatening to commit suicide. “I don’t want to live like this,” he told her after a restless night of little sleep, according to the Sheriff’s Office final report. “I’m going to be a vegetable.”

But the wrongful-death lawsuit that Carol filed in federal court paints a very different picture of events than the Sheriff’s narrative. It states that when Donald saw how distressed Carol was, it softened his resolve. “This is a beautiful day,” Donald told her as he guided both of them to the backyard of their stately home off San Antonio Creek Road. “Let’s just sit and have a nice day.”

Deputies Rogers, Jarrett Morris, and Joseph Schmidt, all of whom had been with the department for less than three years at that time, soon arrived armed with AR-15 rifles. Carol went to meet them at the front door, but the deputies blew right past her.

“They did not ask her any questions,” the lawsuit says. “They did not interview her. They did not assess the situation. They did not evaluate the physical layout of the property. They did not wait for properly trained deputies or for their supervisors to arrive at the scene.” Instead, Rogers and his partners fanned out over the property. As they took their positions, Carol begged them not to scare Donald.

Rogers was supposed to watch the front of the house, but he left his post, walked along a side path to the backyard, and suddenly confronted Donald, who was standing at his walker on a small bedroom patio. He was holding a small silver pistol.

The deputies ordered Donald to drop the gun. He refused, saying something like “No you won’t,” and then pointed it at them, the deputies told investigators. They fired 11 rounds, and Donald fell. The bullets struck his chest, thigh, and forearm and shattered his right femur.

Rogers then jumped onto the patio, stood over Donald, and fired a round, point blank, through his face. Rogers told investigators he did so because Donald appeared to “manipulate” the gun and lift his head to look at him.

Carol’s attorneys argued Donald was likely convulsing from the trauma and glancing around in shock and panic. Rogers described Donald’s eyes as “very large, like he was in a hurry.” Just before the gunfire erupted, Carol said she’d heard her husband, who wasn’t wearing his hearing aids that day, loudly call her name.

The following afternoon, Sheriff Brown told reporters the deputies had acted appropriately. They were forced to make a split-second decision in a life-or-death moment, he said. The District Attorney’s Office deemed the killing a justifiable homicide, citing George’s alleged decision to threaten deputies with a loaded pistol and calling it a clear-cut example of “suicide by cop.”

County attorneys fought tooth and nail for the next five years to quash Carol’s lawsuit. They argued Donald died because of his own “negligence and misconduct.” Federal judges, however, ruled the civil matter should be allowed to proceed to trial because of significant discrepancies in the deputies’ statements to investigators, including which of them spotted Donald first, whom exactly he pointed the gun at, which deputy fired first, and so on. None of the deputies’ audio-video recorders were turned on at the time.

The judges also noted that Donald was shot even though he had not committed a crime; he was not resisting arrest or trying to flee; the domestic disturbance had apparently ended by the time deputies arrived; and he was entitled by the Second Amendment to possess a loaded firearm on his property.

The case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which denied a petition by the county to have it dismissed on immunity grounds. A trial date was scheduled for 2015 in Los Angeles. But before opening statements could begin, Carol accepted a $650,000 settlement from the county that released the deputies and the government from any official wrongdoing.

Carol, a retired schoolteacher, might have been able to secure a larger payout if the litigation had continued, but that wasn’t her priority, those with knowledge of the case have said. She cared more about improving training for sheriff’s employees who encounter disabled and mentally ill people in high-stress situations. No departmental reforms, however, were stipulated in the final agreement.

Santa Barbara Sheriff Deputy Jeremy Rogers Shooting #2

It was July 2, 2012, when a Los Olivos woman caught Matthew Berg burglarizing her home. He’d stolen watches and jewelry, including her deceased husband’s wedding ring, before leading authorities on a winding high-speed chase along Highway 101 and side streets, at times on the wrong side of the road. Rogers again sprang into action.

By the time Rogers caught up to Berg, Berg had shaken the other pursuing deputies and CHP officers and stopped on the south side of the Santa Ynez River Bridge. He was standing, shirtless and shoeless, next to the open trunk of his turquoise Saturn and peering over the edge. It looked as if he were about to toss his loot into the riverbed below.

As Rogers approached, Berg turned his head, and the two locked eyes, according to Rogers’s statement to investigators. Berg ran back to his car, which was facing Rogers. Rogers came to a quick stop, jumped out and drew his gun, and yelled at Berg to surrender. Rogers failed to put his cruiser in park, and it started rolling toward Berg.

Rogers’s training should have told him to either box in Berg between his cruiser and the railing or stop farther back, take cover behind his car, and wait for backup ― not exit his rolling vehicle in the middle of the road.

It appears from Rogers’s dash-cam video that Berg then attempted to steer around the deputy’s driverless car on the narrow two-lane bridge, but Rogers claimed in his interview with detectives that Berg was headed right for him. “He would have run me over and possibly killed me,” he said. “I believe that’s what he was trying to do.” Berg, 47 years old and from Santa Maria, had a long rap sheet of arrests and jail stints, though never for any violent crimes.

Rogers also told investigators that as Berg came closer, he seemed to reach for a weapon. Berg was in fact not armed. Rogers opened fire, putting eight quick rounds through the Saturn’s windshield and hood and hitting Berg in the face, shoulders, and chest.

Rogers’s dash-cam clearly captured the shooting, though the Sheriff’s Office initially told the Independent the shooting had occurred outside of the camera’s view. Only after being pressed by the Independent did the department provide the video. That copy, however, blurs out Berg for the entirety of the incident and ends shortly after Rogers stops firing. The Sheriff’s Office has not explained why the video was edited. (Recently released dash-cam videos that the department provided to the Independent of other law enforcement shootings, including those of Michael Ledesma and Bryan Carreño, were not edited.)

In 2012, Berg’s sister, Debbie Quisenberry, watched an unaltered version of the footage obtained by her attorneys when she was considering filing an excessive-force lawsuit against Rogers. In a letter previously published by the Independent, Quisenberry claimed Berg’s arms were raised when he was shot.

Quisenberry also wrote how she was struck by the “complete lack of regard for human life” displayed by Rogers and his colleagues as Berg’s head lolled back and forth and he bled out in his seat. “The officers were clearly happy with Rogers’s performance,” she said. “They are seen slapping Rogers on the back for a job well done, and Rogers is seen strutting with pride over his kill.” None of them, she said, made any effort to save her brother’s life.

“That day, Matt had committed a crime,” Quisenberry said, “but he did not deserve to die.”

Quisenberry ultimately did not file a lawsuit because she couldn’t afford the legal fees. But she said she remains haunted that a “trigger-happy” deputy continues to patrol Santa Barbara with impunity. “Rogers still carries a gun and is still out there ‘Protecting and Serving,’” she said.

As in the case of Donald George, the Sheriff’s Office determined Rogers had used a reasonable amount of force to protect himself and others against what he perceived to be an imminent threat. Authorities noted that Berg had put many motorists at serious risk during his high-speed chase that at times exceeded 100 mph.

In her final report, District Attorney Joyce Dudley quoted from the majority opinion delivered by the U.S. Supreme Court in a precedent-setting excessive-force case from 1989. “We must never allow the theoretical, sanitized world of our imagination to replace the dangerous and complex world that policemen face everyday,” the justices wrote in Graham v. Connor. “What constitutes ‘reasonable’ action may seem quite different to someone facing a possible assailant than to someone analyzing the question at leisure.”

Santa Barbara Sheriff Deputy Jeremy Rogers Shooting #3

The October 15, 2019, shooting death of Cameron Ely by four deputies, including Rogers, remains an open case. As a result, little information is publically available.

Sheriff’s officials have only divulged that Cameron ― the 30-year-old son of Tarzan actor Ron Ely ― stabbed his mother to death at the family’s Hope Ranch estate, then called 9-1-1 to try to blame the murder on his father. “The caller was out of breath, unintelligible, and crying,” a 9-1-1 dispatcher said in a radio communication to nearby units. When the deputies arrived, they found Ron inside unharmed and Cameron outdoors.

“The suspect told deputies that he had a gun, advanced towards the deputies, and motioned with his hands as if he were drawing a weapon,” the Sheriff’s Office said in a media statement at the time. “In response, four deputies fired a total of 24 rounds from their service weapons, fatally wounding the suspect. When deputies were able to safely approach Cameron using a ballistic shield, they found that he had feigned being armed and did not have a weapon.”

Two months later, a member of Santa Barbara’s law enforcement community leaked an audio recording of the encounter to news organizations. The clip begins with the deputies ― Sergeant Desiree Thome, Deputy Phillip Farley, Deputy John Gruttadaurio, and Rogers ― first confronting Cameron. “Hey!” Rogers yells. “We got somebody over here!”

“Keep your hands up, okay?” another deputy gently says to Cameron. “Keep your hands up.” There is no audible response from Cameron and no clear indication when he told the deputies he was armed.

“You got gloves?” one deputy asks another. Cameron was flecked with blood. “We need somebody to glove up … [radio cross-talk]. Standby.”

A couple beats of silence pass before a sudden cacophony of gunfire. “Fuck!” Rogers yells right after. Then, a few moments later, he yells again: “He’s still moving! There’s a gun under him!”

The lone female-sounding voice, which likely belongs to Sergeant Desiree Thome, cuts in. “One person give him instructions,” she says calmly. Rogers shouts at Cameron to move his right hand out from under his body. No response. The order is repeated. Again, no response. The recording ends. It’s also not clear at what point in the encounter Cameron had “advanced” on the deputies.

Cameron Ely attended Harvard University, where he played football and graduated with a psychology degree in 2012. He worked as a security guard for two years before his death.

Be sure to check out SANTA BARBARA SHERIFF DEPARTMENT